What does it mean to be "sh compatible"?

Why are there so many "sh compatible" shells?

The Bourne shell was first publicly released in 1979 as part of Unix V7. Since pretty much every Unix and Unix-like system descends from V7 Unix — even if only spiritually — the Bourne shell has been with us "forever."¹

The Bourne shell actually replaced an earlier shell, retronymed the Thompson shell, but it happened so early in Unix's history that it's all but forgotten today. The Bourne shell is a superset of the Thompson shell.²

Both the Bourne and Thompson shells were called sh. The shell specified by POSIX is also called sh. So, when someone says sh-compatible, they are handwavingly referring to this series of shells. If they wanted to be specific, they'd say "POSIX shell" or "Bourne shell."³

The POSIX shell is based on the 1988 version of KornShell, which in turn was meant to replace the Bourne shell on AT&T Unix, leapfrogging the BSD C shell in terms of features.⁴ To the extent that ksh is the ancestor of the POSIX shell, most Unix and Unix-like systems include some variant of the Korn shell today. The exceptions are generally tiny embedded systems, which can't afford the space a complete POSIX shell takes.

That said, the Korn shell — as a thing distinct from the POSIX shell — never really became popular outside the commercial Unix world. This is because its rise corresponded with the early years of Unix commercialization, so it got caught up in the Unix wars. BSD Unixes eschewed it in favor of the C shell, and its source code wasn't freely available for use in Linux when it got started.⁵ So, when the early Linux distributors went looking for a command shell to go with their Linux kernel, they usually chose GNU Bash, one of those sh-compatibles you're talking about.⁶

That early association between Linux and Bash pretty much sealed the fate of many other shells, including ksh, csh and tcsh. There are die-hards still using those shells today, but they're very much in the minority.⁷

All this history explains why the creators of relative latecomers like bash, zsh, and yash chose to make them sh-compatible: Bourne/POSIX compatibility is the minimum a shell for Unix-like systems must provide in order to gain widespread adoption.

In many systems, the default interactive command shell and /bin/sh are different things. /bin/sh may be:

The original Bourne shell. This is common in older UNIX® systems, such as Solaris 10 (released in 2005) and its predecessors.⁸

A POSIX-certified shell. This is common in newer UNIX® systems, such as Solaris 11 (2010).

The Almquist shell. This is an open source Bourne/POSIX shell clone originally released on Usenet in 1989, which was then contributed to Berkeley's CSRG for inclusion in the first BSD release containing no AT&T source code, 4.4BSD-Lite. The Almquist shell is often called

ash, even when installed as/bin/sh.4.4BSD-Lite in turn became the base for all modern BSD derivatives, with

/bin/shremaining as an Almquist derivative in most of them, with one major exception noted below. You can see this direct descendancy in the source code repositories for NetBSD and FreeBSD: they were shipping an Almquist shell derivative from day 1.There are two important

ashforks outside the BSD world:dash, famously adopted by Debian and Ubuntu in 2006 as the default/bin/shimplementation. (Bash remains the default interactive command shell in Debian derivatives.)The

ashcommand in BusyBox, which is frequently used in embedded Linuxes and may be used to implement/bin/sh. Since it postdatesdashand it was derived from Debian's oldashpackage, I've chosen to consider it a derivative ofdashrather thanash, despite its command name within BusyBox.(BusyBox also includes a less featureful alternative to

ashcalledhush. Typically only one of the two will be built into any given BusyBox binary:ashby default, buthushwhen space is really tight. Thus,/bin/shon BusyBox-based systems is not alwaysdash-like.)

GNU Bash, which disables most of its non-POSIX extensions when called as

sh.This choice is typical on desktop and server variants of Linux, except for Debian and its derivatives. Mac OS X has also done this since Panther, released in 2003.

A shell with

ksh93POSIX extensions, as in OpenBSD. Although the OpenBSD shell changes behavior to avoid syntax and semantic incompatibilities with Bourne and POSIX shells when called assh, it doesn't disable any of its pure extensions, being those that don't conflict with older shells.This is not common; you should not expect

ksh93features in/bin/sh.

I used "shell script" above as a generic term meaning Bourne/POSIX shell scripting. This is due to the ubiquity of Bourne family shells. To talk about scripting on other shells, you need to give a qualifier, like "C shell script." Even on systems where a C family shell is the default interactive shell, it is better to use the Bourne shell for scripting.

It is telling that when Wikipedia classifies Unix shells, they group them into Bourne shell compatible, C shell compatible, and "other."

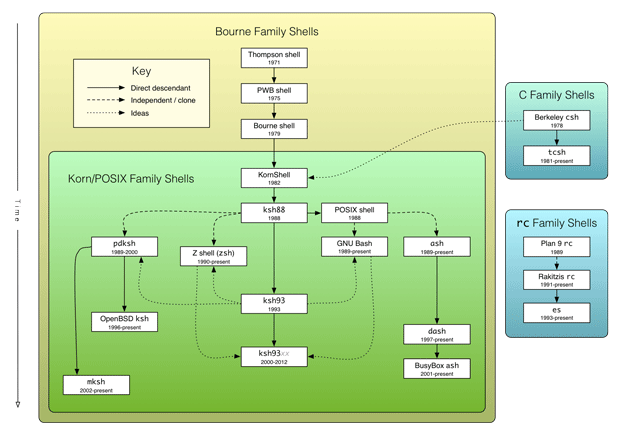

This diagram may help:

(Click for SVG version, 31 kB, or view full-size PNG version, 218 kB.)

What would it mean to be "sh incompatible"?

Someone talking about an sh-incompatible thing typically means one of three things:

They are referring to one of those "other" shells.⁹

They are making a distinction between the Bourne and C shell families.

They are talking about some specific feature in one Bourne family shell that isn't in all the other Bourne family shells.

ksh93,bash, andzshin particular have many features that don't exist in the older "standard" shells. Those three are also mutually-incompatible in a lot of ways, once you get beyond the shared POSIX/ksh88base.

It is a classic error to write a shell script with a #!/bin/sh shebang line at the top but to use Bash or Korn shell extensions within. Since /bin/sh is one of the shells in the Korn/POSIX family diagram above on so many systems these days, such scripts will work on the system they are written on, but then fail on systems where /bin/sh is something from the broader Bourne family of shells. Best practice is to use #!/bin/bash or #!/bin/ksh shebang lines if the script uses such extensions.

There are many ways to check whether a given Bourne family shell script is portable:

Run

checkbashismson it, a tool from the Debian project that checks a script for "bashisms."Run it under

posh, a shell in the Debian package repository that purposely implements only features specified by SUS3, plus a few other minor features.Run it under

oboshfrom the Schily Tools project, an improved version of the Bourne shell as open sourced by Sun as part of OpenSolaris in 2005, making it one of the easiest ways to get a 1979 style Bourne shell on a modern computer.The Schily Tools distribution also includes

bosh, a POSIX type shell with many nonstandard features, but which may be useful for testing the compatibility of shell scripts intended to run on all POSIX family shells. It tends to be more conservative in its feature set thanbash,zshand the enhanced versions ofksh93.Schily Tools also includes a shell called

bsh, but that is an historical oddity which is not a Bourne family shell at all.Go through the Portable Shell Programming chapter in the GNU Autoconf manual. You may recognize some of the problematic constructs it talks about in your scripts.

Why are they different?

For the same reasons all "New & Improved!" things are different:

The improved version could only be improved by breaking backwards compatibility.

Someone thought of a different way for something to work, which they like better, but which isn't the same way the old one worked.

Someone tried reimplementing an old standard without completely understanding it, so they messed up and created an unintentional difference.

Footnotes and Asides:

Early versions of BSD Unix were just add-on software collections for V6 Unix. Since the Bourne shell wasn't added to AT&T Unix until V7, BSD didn't technically start out having the Bourne shell. BSD's answer to the primitive nature of the Thompson shell was the C shell.

Nevertheless, the first standalone versions of BSD (2.9BSD and 3BSD) were based on V7 or its portable successor UNIX/32V, so they did include the Bourne shell.

(The 2BSD line turned into a parallel fork of BSD for Digital's PDP minicomputers, while the 3BSD and 4BSD lines went on to take advantage of newer computer types like Vaxen and Unix workstations. 2.9BSD was essentially the PDP version of 4.1cBSD; they were contemporaneous, and shared code. PDPs didn't just disappear when the VAX arrived, so the 2BSD line is still shambling along.)

It is safe to say that the Bourne shell was everywhere in the Unix world by 1983. That's a good approximation to "forever" in the computing industry. MS-DOS got a hierarchical filesystem that year (awww, how cuuute!) and the first 24-bit Macintosh with its 9" B&W screen — not grayscale, literally black and white — wouldn't come out until early the next year.

The Thompson shell was quite primitive by today's standards. It was only an interactive command shell, rather than the script programming environment we expect today. It did have things like pipes and I/O redirection, which we think of as prototypically part of a "Unix shell," so that we think of the MS-DOS command shell as getting them from Unix.

The Bourne shell also replaced the PWB shell, which added important things to the Thompson shell like programmability (

if,switchandwhile) and an early form of environment variables. The PWB shell is even less well-remembered than the Thompson shell since it wasn't part of every version of Unix.When someone isn't specific about POSIX vs Bourne shell compatibility, there is a whole range of things they could mean.

At one extreme, they could be using the 1979 Bourne shell as their baseline. An "

sh-compatible script" in this sense would mean it is expected to run perfectly on the true Bourne shell or any of its successors and clones:ash,bash,ksh,zsh, etc.Someone at the other extreme assumes the shell specified by POSIX as a baseline instead. We take so many POSIX shell features as "standard" these days that we often forget that they weren't actually present in the Bourne shell: built-in arithmetic, job control, command history, aliases, command line editing, the

$()form of command substitution, etc.Although the Korn shell has roots going back to the early 1980s, AT&T didn't ship it in Unix until System V Release 4 in 1988. Since so many commercial Unixes are based on SVR4, this put

kshin pretty much every relevant commercial Unix from the late 1980s onward.(A few weird Unix flavors based on SVR3 and earlier held onto pieces of the market past the release of SVR4, but they were the first against the wall when the revolution came.)

1988 is also the year the first POSIX standard came out, with its Korn shell based "POSIX shell." Later, in 1993, an improved version of the Korn shell came out. Since POSIX effectively nailed the original in place,

kshforked into two major versions:ksh88andksh93, named after the years involved in their split.ksh88is not entirely POSIX-compatible, though the differences are small, so that some versions of theksh88shell were patched to be POSIX-compatible. (This from an interesting interview on Slashdot with Dr. David G. Korn. Yes, the guy who wrote the shell.)ksh93is a fully-compatible superset of the POSIX shell. Development onksh93has been sporadic since the primary source repository moved from AT&T to GitHub with the newest release being about 3 years old as I write this, ksh93v. (The project's base name remainsksh93with suffixes added to denote release versions beyond 1993.)Systems that include a Korn shell as a separate thing from the POSIX shell usually make it available as

/bin/ksh, though sometimes it is hiding elsewhere.When we talk about

kshor the Korn shell by name, we are talking aboutksh93features that distinguish it from its backwards-compatible Bourne and POSIX shell subsets. You rarely run across the pureksh88today.AT&T kept the Korn shell source code proprietary until March 2000. By that point, Linux's association with GNU Bash was very strong. Bash and

ksh93each have advantages over the other, but at this point inertia keeps Linux tightly associated with Bash.As to why the early Linux vendors most commonly choose GNU Bash over

pdksh, which was available at the time Linux was getting started, I'd guess it's because so much of the rest of the userland also came from the GNU project. Bash is also somewhat more advanced thanpdksh, since the Bash developers do not limit themselves to copying Korn shell features.Work on

pdkshstopped about the time AT&T released the source code to the true Korn shell. There are two main forks that are still maintained, however: the OpenBSDpdkshand the MirBSD Korn Shell,mksh.I find it interesting that

mkshis the only Korn shell implementation currently packaged for Cygwin.GNU Bash goes beyond POSIX in many ways, but you can ask it to run in a more pure POSIX mode.

csh/tcshwas usually the default interactive shell on BSD Unixes through the early 1990s.Being a BSD variant, early versions of Mac OS X were this way, through Mac OS X 10.2 "Jaguar". OS X switched the default shell from

tcshto Bash in OS X 10.3 "Panther". This change did not affect systems upgraded from 10.2 or earlier. The existing users on those converted systems kept theirtcshshell.FreeBSD claims to still use

tcshas the default shell, but on the FreeBSD 10 VM I have here, the default shell appears to be one of the POSIX-compatible Almquist shell variants. This is true on NetBSD as well.OpenBSD uses a fork of

pdkshas the default shell instead.The higher popularity of Linux and OS X makes some people wish FreeBSD would also switch to Bash, but they won't be doing so any time soon for philosophical reasons. It is easy to switch it, if this bothers you.

It is rare to find a system with a truly vanilla Bourne shell as

/bin/shthese days. You have to go out of your way to find something sufficiently close to it for compatibility testing.I'm aware of only one way to run a genuine 1979 vintage Bourne shell on a modern computer: use the Ancient Unix V7 disk images with the SIMH PDP-11 simulator from the Computer History Simulation Project. SIMH runs on pretty much every modern computer, not just Unix-like ones. SIMH even runs on Android and on iOS.

With OpenSolaris, Sun open-sourced the SVR4 version of the Bourne shell for the first time. Prior to that, the source code for the post-V7 versions of the Bourne shell was only available to those with a Unix source code license.

That code is now available separately from the rest of the defunct OpenSolaris project from a couple of different sources.

The most direct source is the Heirloom Bourne shell project. This became available shortly after the original 2005 release of OpenSolaris. Some portability and bug fixing work was done over the next few months, but then development on the project halted.

Jörg Schilling has done a better job of maintaining a version of this code as

oboshin his Schily Tools package. See above for more on this.Keep in mind that these shells derived from the 2005 source code release contain multi-byte character set support, job control, shell functions, and other features not present in the original 1979 Bourne shell.

One way to tell whether you are on an original Bourne shell is to see if it supports an undocumented feature added to ease the transition from the Thompson shell:

^as an alias for|. That is to say, a command likels ^ morewill give an error on a Korn or POSIX type shell, but it will behave likels | moreon a true Bourne shell.Occasionally you encounter a

fish,scshorrc/esadherent, but they're even rarer than C shell fans.The

rcfamily of shells isn't commonly used on Unix/Linux systems, but the family is historically important, which is how it earned a place in the diagram above.rcis the standard shell of the Plan 9 from Bell Labs operating system, a kind of successor to 10th edition Unix, created as part of Bell Labs' continued research into operating system design. It is incompatible with both Bourne and C shell at a programming level; there's probably a lesson in there.The most active variant of

rcappears to be the one maintained by Toby Goodwin, which is based on the Unixrcclone by Byron Rakitzis.

"sh compatible" refers to POSIX sh, the basic shell that is required to exist on all compatible systems. A sh-compatible script should work on any POSIX-compatible machine.

The reason it's necessary to say so is that commonly /bin/sh is a symlink to /bin/bash, which has let some Bashisms slip into scripts that declare themselves to use sh with #!/bin/sh. These scripts fail to work on systems that don't use bash as /bin/sh, including some commercial Unices forever, and Debian and derivatives recently.

In particular there's been a trend to use dash, the Debian Almquish Shell, as the default sh lately, because it's smaller and meant to be faster. That trend has highlighted a lot of those Bashisms that were in supposed sh scripts. Describing something as "sh compatible" indicates that it's explicitly intended to work with these systems by staying entirely within the POSIX-specified language — all shells will implement a superset of that functionality, so it's guaranteed to work everywhere, but their extensions aren't compatible with one another.

Different shells have their own development histories and diverged in different directions over time, as they added functions to help interactive use for their users, or scripting extensions like associative arrays. A "sh-incompatible" script would use some of these non-standard extension features, like Bash's [[ conditionals.

The non-POSIX features in bash and tcsh and zsh and all of the other current shells are useful, and there are plenty of occasions where you might want or need them. They just shouldn't be used in a script that declares itself to work with /bin/sh, because you can't rely on those features being in the base sh implementation on the system you're running on.

A script that does need to use, say, associative arrays, should ensure it's run with bash rather than sh:

#!/bin/bash

declare -A array

That will work anywhere with bash. Scripts that don't need the extended functionality and are meant to be portable should declare that they use sh and stick to the base shell command language.